Our approach to video has been estimated to save ~$2.4M per $10M spent on paid video. And for organic content, our first YouTube pilot, which was on a channel with 1.4M subscribers, yielded the most-viewed video on the channel (a title it held for over a year).

But how do we do it? The trick is to get others to pay for failure. That’s basically it… you can stop reading here if you’d like. But if you want to learn more details and the story for how we got here (as written by TCD and not GPT), read on.

While working as a Sr. Quant at Bloomberg; then later, a data science consultant to GroupM TV; and later, as Head of TV optimization for Tripadvisor and founder of the Performance TV Group in Boston, one of the issues I kept noticing across brands was the high failure rate of video content. Brands spend millions – some BILLIONS – on their TV & video campaigns, only to be shocked when their foundational video concept behind all the spend underperforms.

I’ve lived these shocks first hand. Many brands don’t even realize the root cause of the lackluster video performance, often looking instead at media costs. My desire to solve this problem led to Videoquant, but not without many failures and lessons along the way. Here’s some of what I learned:

Lesson 1: Most video performs weakly. This includes TV commercials and social videos such as organic YouTube content.

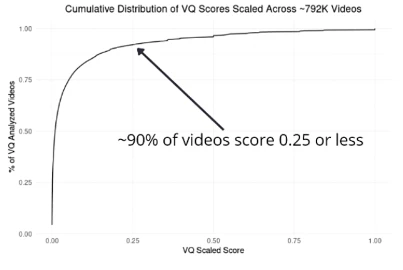

Our analysis of data on over 10 million TV commercials and videos reveals a startling fact: only around 10% of video content effectively drives engagement, indicating a 90% failure rate. No engagement means no return on investment (ROI). The accompanying plot, derived from one of our foundational slide decks, underscores how infrequently videos achieve decent performance levels (> 0.25 on a 0 to 1 scale). This finding aligns with broader analyses, confirming the inherent difficulty in succeeding with video content.

Indeed, there’s an irony here. It turns out that most marketing channels – not just video – have high failure rates. While video’s rate seems slightly higher, it’s not drastically different from other channels. A good friend of mine, who is among the best in the industry, recently disclosed that around 80% of his website optimization tests fail. So, failure in marketing is not uncommon, and video is not an exception in that regard. However, what sets video apart is the (1) higher upfront cost to build content, (2) audiovisual storytelling complexity requiring more tests to optimize, and (3) high pivot costs. These factors amplify each other, escalating the investment required before there’s sufficient data to realize a video strategy is off course (more on this below). In other words, it’s cheap and fast to test, fail, then try again on most channels. Not so with video – it has a high “Cost To Learn.”

Lesson 2: Video content, not media, is usually the driver of video success.

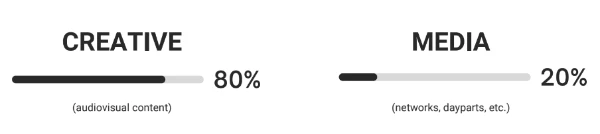

While this lesson might be second nature to social video creators, it’s frequently less evident to TV and paid video advertisers, who often scrutinize their largest cost centers, such as media agencies and platforms, first. We tested and found that ~80% of how well a video performs on meaningful performance metrics is tied to the video content (the audiovisual that people are viewing). Yet, this is the area that often receives the least data scrutiny in video marketing. While most brands are spending enormous resources optimizing their media spend (where their video runs and how much they are paying for it), video content is the proverbial horse in the race. It seems most brands are racing 3-legged horses, often with top-tier media jockeys.

This result is fairly easy to replicate for almost any brand using their data. For my data scientists reading this, think about how you’d measure this. Send us your thoughts using the “Contact Us” page.

Lesson 3: Guessing is the predominant driver of video content today.

Today, most video content, including everything from YouTube content to polished Super Bowl TV ads, is dictated by guessing or qualitative methods that poorly correlate with real-world video performance. While savvier brands use methods such as surveys, focus groups, and panel studies to gain insights into what video content to build, these methods are untethered from true video consumption and don’t reliably assess which video content is likely to work.

Some brands turn to media measurement tools such as iSpot, Nielsen, and Comscore, but these only provide retrospective analyses at too high a granularity for video, offering no insights into why a video performed poorly, what content may perform better, or how to improve future campaigns, and this comes after you’ve already incurred the costs of failed tests . Additionally, some newer tools that do aim to provide such video creative insights either rely, behind the scenes, on the same flawed qualitative methods like panels, focus groups, or surveys, and/or they use the brand’s own data. The problem with this latter case is the data is too limited – you haven’t run the tests – to unwind the myriad variables affecting video performance (see lesson 4).

As a consequence of these limitations, what we often observe in practice is the loudest voice in the boardroom driving core content decisions for major brands, whether it’s the brand’s or ad agency’s boardroom. For social video creators, the video is often influenced more by what the creator wants to build or what others ask the creator to build rather than by solid data indicating what is most likely to succeed. In any of these cases, human intuition is driving video content, and the data shows that intuition leaves a lot of cash on the table.

Lesson 4: Unlike other marketing, testing to learn with video is highly inefficient.

Unlike other mediums like search engine optimization where, for near zero costs, thousands of tests can be launched in single day to learn what works, this isn’t feasible with video due to its complexity. And when I say complexity, there are 2 distinct types of complexity: (1) Video has a higher upfront cost to build, and (2) video has more levers (parameters) that need to be optimized. As a result, the preamble to our first patent app was the calculation that the cost to learn what works for TV is roughly 1800x greater than the cost of comparable SEM (search engine marketing) learnings.

The Secret Sauce Revealed

After years of looking at this problem, what I realized was that the only way to win with video is we needed to lower the 1800x video “cost to learn.” If we could tackle the 1800x multiple and bring that down to maybe 2x or, heck, even a 10x multiple of SEM, we could win on TV and social video.

This thinking led to the “aha” moment. The trick, or the secret sauce, is to have others pay for our testing. You see, marketing tests are happening all around us every day. Whether you like it or not, you are part of multiple experiments right now as you are reading this. Everything from what comes up in Google when you search, to what you hear on the car radio, to what you are watching on TV is being decided by brands running tests to deliver better performance. Chances are, if you have an idea for a video or TV commercial, something like it has already been tried by someone else. By tapping into all those tests, we can gain insight into how a video will perform without paying to run that test ourselves. Enter “Competitor-funded video R&D”. How exactly to do this is what we eventually applied for patents on.

This insight was the breakthrough, although it took about 4 more breakthroughs to make it work. But shortly thereafter, the first prototype was written and backtesting showed it *should* work where earlier attempts of ours had failed. We soon had our first proof of concept where we delivered a video concept to a 1.4M subscriber YouTube channel that soon became its top channel performer. We went from *it should* to *it did* work (well, at least once at that point). We then filed our second, third and fourth patent applications, which cover all aspects related to optimizing video content through this novel method.

What we found along the way is that, even using this approach, it’s very hard to predict video that will go viral. But we don’t need to. It’s an easier problem to predict videos (and ideas for videos) unlikely to work. And that is Videoquant’s main mode of driving cost savings – eliminating & reducing spend on video concepts and executions that have a track record of poor performance learned through investments made by others.

So that’s all I have today, folks. The rest of the story is being written as I write this. Cheers! -Tim